More than clogged drains, it is failed governance and unchecked urban chaos that keep Karachi underwater

Record-setting monsoon rains that hit Karachi in August 2025 were not just a local disaster—they were part of a wider wave of urban flooding across Pakistan. This very season, cities from Lahore to Islamabad, Faisalabad to Multan, saw streets turn into rivers as drainage systems collapsed under the pressure of intense downpours. Lack of urban planning and deforestation among others are also reasons. But the common thread: clogged storm drains, governance failures, and irritated citizens. Karachi’s ordeal, therefore, was both a local tragedy and a national warning.

Karachi has been time and again reminded of the fragile state of its urban infrastructure. In just a few hours on August 19, rainfall peaked in parts of the city at over 170 mm, far beyond the 40 mm capacity of Karachi’s drainage system. Main arteries like Shahrah-e-Faisal, MA Jinnah Road, and II Chundrigar Road were quickly submerged; vehicles and commuters found themselves stranded in tens of thousands, and daily life ground to a halt.

The torrential downpour unleashed human tragedy as well as infrastructural failure. Deaths were reported from all over the city. The situation was dire: power outages and mobile network disruptions left many citizens trapped and isolated. Amid this, rescue teams and municipal staff worked relentlessly to clear flooded streets and restore essential services.

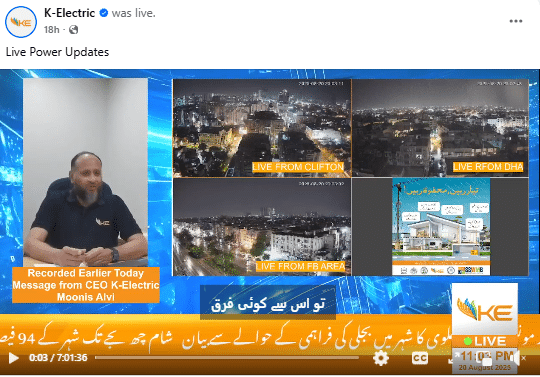

Yet, amid chaos, it was the response or lack thereof from different authorities that revealed the city’s deeper challenges. K-Electric emerged as one of the few institutions to act decisively. It shut down feeders only where safety required it and restored power as soon as water receded. The utility also provided regular updates via helplines and social media, demonstrating a level of operational transparency sorely absent elsewhere.

By contrast, the situation in Sindh’s interior was far worse. Under HESCO (Hyderabad Electric Supply Company) and SEPCO (Sukkur Electric Power Company), entire districts plunged into prolonged blackouts as feeders tripped and restoration dragged on for days. In Hyderabad, parts of Latifabad and Qasimabad remained without power for more than 48 hours, while in Sukkur and Larkana, residents reported outages stretching beyond three days. The absence of timely communication from both utilities deepened public frustration, underscoring the stark difference in crisis management between Karachi and other parts of the province.

https://x.com/Arfana_Mallah/status/1958235265568555455?t=xqNLPank4sU8fdydH65RJA&s=19

https://x.com/AnsariFaisee76/status/1959266782302323172?t=_yAOqmiSEL2VbdlrzJgNtw&s=19

https://x.com/BabarAliBozdar/status/1957099686571241690?t=0FZE-k6OXgzSeTEQ1Dxt-w&s=19

Equally inspiring, however, was the role of ordinary citizens. Across the city, volunteers and local businesses displayed acts of generosity that captured Karachi’s spirit. Restaurants opened their doors to stranded commuters, tea vendors offered shelter from the rain, and residents welcomed neighbours and strangers alike into their homes. Self-appointed helpers guided stuck vehicles, supported traffic police, and turned flooded streets into makeshift sites of solidarity. These acts, though small in scale, carried immense weight in a city where collective resilience often substitutes for institutional preparedness.

https://www.instagram.com/p/DNiHQFfBzbu/?hl=en

https://www.instagram.com/p/DNijh5ZKrCD/?hl=en

https://www.facebook.com/share/v/1BEkzEon3R/

https://www.facebook.com/share/v/18jUPkjMtH/?mibextid=wwXIfr

But the crisis also exposed glaring absences. Political leadership, which should be central to both pre-emptive planning and on-ground presence, was largely invisible. Urban planners and regulators who have allowed unchecked encroachments on storm drains, weakening the city’s drainage capacity, were nowhere to be seen when those same drains overflowed. The Sindh Building Control Authority and other enforcement bodies, whose neglect directly contributes to flooding, were absent from public visibility and accountability.

Beyond poor governance, Karachi’s very design makes it vulnerable. A metropolis of over 20 million people operates without an integrated urban drainage and stormwater management system. Roads double as water channels, storm drains are routinely choked by garbage, and entire settlements are built directly on natural nullahs. The case of Gujjar Nullah and Orangi Nullah illustrates decades of unchecked encroachment narrowed water pathways, leaving no room for excess rainwater to escape. Even after partial clearance drives in 2021, rehabilitation stalled, and flooding has remained a recurring nightmare for nearby residents.

Compare this with Kuala Lumpur, which invested in the SMART Tunnel, a dual-purpose roadway and flood-control channel that diverts stormwater within minutes, preventing major flooding in the city. Similarly, Dubai has implemented advanced pumping stations and underground reservoirs that ensure water never lingers on major roads despite heavy rains. Karachi, by contrast, remains reactive patching together emergency clean-ups every monsoon instead of building durable, engineered solutions.

Equally troubling was the limited role of national agencies tasked with disaster preparedness. While the Pakistan Meteorological Department and the National Disaster Management Authority issued advisories, these warnings failed to translate into meaningful action on the ground. Once again, Karachi was left in a reactive posture—scrambling to manage floodwaters instead of preventing them. The contrast could not have been sharper: while frontline workers, utility staff, and ordinary citizens braved the storm, those responsible for long-term infrastructure planning and governance remained out of sight.

In fact, the same story unfolded in other cities. Lahore’s Gulberg and Johar Town neighborhoods were submerged within hours of heavy rain; Islamabad’s I-8 and Blue Area came to a standstill; Faisalabad and Multan saw entire residential colonies flooded as drains overflowed. Everywhere, the response was reactive, not preventive. These repeated failures underscore that Karachi’s ordeal is not unique—it is a symptom of Pakistan’s larger urban crisis.

For many observers, this underlined a sobering reality: Karachi is resilient not because of strong systems, but despite weak ones. The city survives on the dedication of its responders and the improvisation of its people, but without decisive leadership and investment in drainage and urban planning, the same cycle of paralysis and recovery will return with every downpour. And unless Pakistan’s other cities learn from this experience, they too, will continue to lurch from one monsoon disaster to the next.

Resilience, while admirable, cannot remain the only strategy. The monsoon of 2025 has made it clear that Pakistan’s cities need transformation, not just recovery. Lasting investment in stormwater management, strict enforcement against encroachments, and climate-smart infrastructure are no longer optional—they are essential for survival.