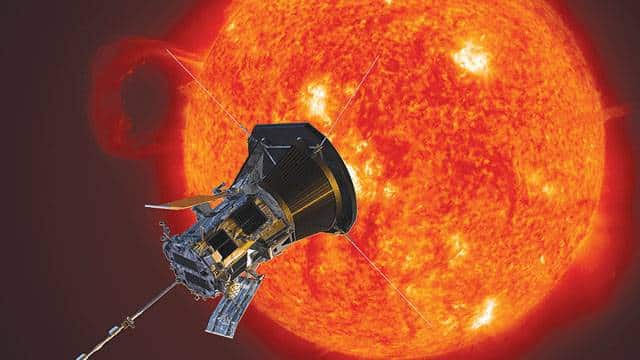

The Parker Solar Probe, launched by NASA in 2018, is on a groundbreaking mission to explore the Sun, culminating in a historic flyby on 24 December of the coming year. Racing at an astonishing speed of 195 km/s, or 435,000 mph, the probe will get within 6.1 million km, or 3.8 million miles, of the Sun’s surface – an unparalleled proximity that no human-made object has ever achieved. Dr. Nour Raouafi, the project scientist, describes it as “almost landing on a star,” comparing it to the monumental achievement of the Moon landing in 1969.

The Parker Solar Probe’s audacious goal is to make repeated, progressively closer passes of the Sun, with the upcoming maneuver bringing it to just 4% of the Sun-Earth distance. This ambitious approach is not without challenges, as at its closest point, the probe will face temperatures reaching 1,400°C due to the Sun’s intense gravitational pull. To endure these extreme conditions, Parker adopts a strategy of swift in-and-out movements, utilizing a suite of instruments behind a robust heat shield to make crucial measurements of the solar environment.

The primary objective is to gain a deeper understanding of the Sun’s outer atmosphere, the corona, where temperatures soar unexpectedly to over a million degrees. This counterintuitive superheating and the acceleration of charged particles within the corona remain enigmatic phenomena. Scientists hope that the data collected by Parker will unravel these mysteries, providing essential insights for improving solar behavior forecasts and enhancing our understanding of “space weather.” Such forecasts are crucial for mitigating the impacts of solar eruptions on Earth’s communication systems and power grids, as well as addressing health risks for astronauts.

As the mission reaches its apex in the coming year, with close approaches and a lengthy sojourn in the corona, researchers anticipate groundbreaking discoveries about solar processes. The information gathered during the historic 24 December flyby, where Parker will spend an extended period in the corona, offers a unique opportunity to study potential waves in the solar wind associated with the heating phenomenon. While the probe won’t be able to get any closer to the Sun after December, the data amassed is expected to contribute significantly to our understanding of the Sun and its impact on space weather, with implications for future lunar exploration and human presence beyond Earth.